“A lot of strange things happen in this world. Things you don’t know about in grand Rapids.“

Paul Schrader is a unique figure in cinema. Despite being behind the camera on a string of well-regarded films spanning almost 50 years, most film fans will know Schrader as the scribe of four Martin Scorsese films – including Taxi Driver and the severely underrated Nicolas Cage-starrer Bringing Out the Dead. With their focus on the seedy underbelly of New York through the eyes of the mentally unstable, the films make a cracking double feature. But perhaps most film fans these days, will know Schrader as the crotchety old Grandpa on Facebook. Whether he’s voicing his opinion on the aspects of modern culture he can’t understand or his experiences with Ozempic, Schrader’s FB posts have made him the go to meme of #FilmTwitter. Check out the fantastic @paul_posts on Twitter for more of Schrader’s characteristically polarising opinions.

But as well as the memes, Schrader’s filmography has had something of a resurgence and reappraisal over the past few years. Firstly, Schrader returned to the forefront of awards seasons and critical acclaim in 2017 with his fantastic and harrowing eco/religious thriller, First Reformed. This was the first of what Schrader refers to as his ‘man in a room’ trilogy. If you’re watching a film featuring a troubled and tattooed man, writing nihilistic statements into his journal and speaking in voice-over, you’re probably watching a late-career Paul Schrader film. Schrader followed First Reformed with The Card Counter, a film ostensibly about gambling but which was actually about the treatment of prisoners at Abu Ghraib. The Card Counter wasn’t quite as lauded as First Reformed, but it was still a highlight of 2021, with Schrader’s direction and Oscar Isaac’s central performance being lauded. Schrader has since completed his trilogy with Master Gardener, starring Joel Egerton as a Proud Boy whistle-blower turned troubled gardener. He’s got a new film in the works with Richard Gere (who Schrader worked with on American Gigolo in 1980) and has proposed scripts for Antoine Fuqua and Elizabeth Moss to direct. Schrader is not slowing down any time soon.

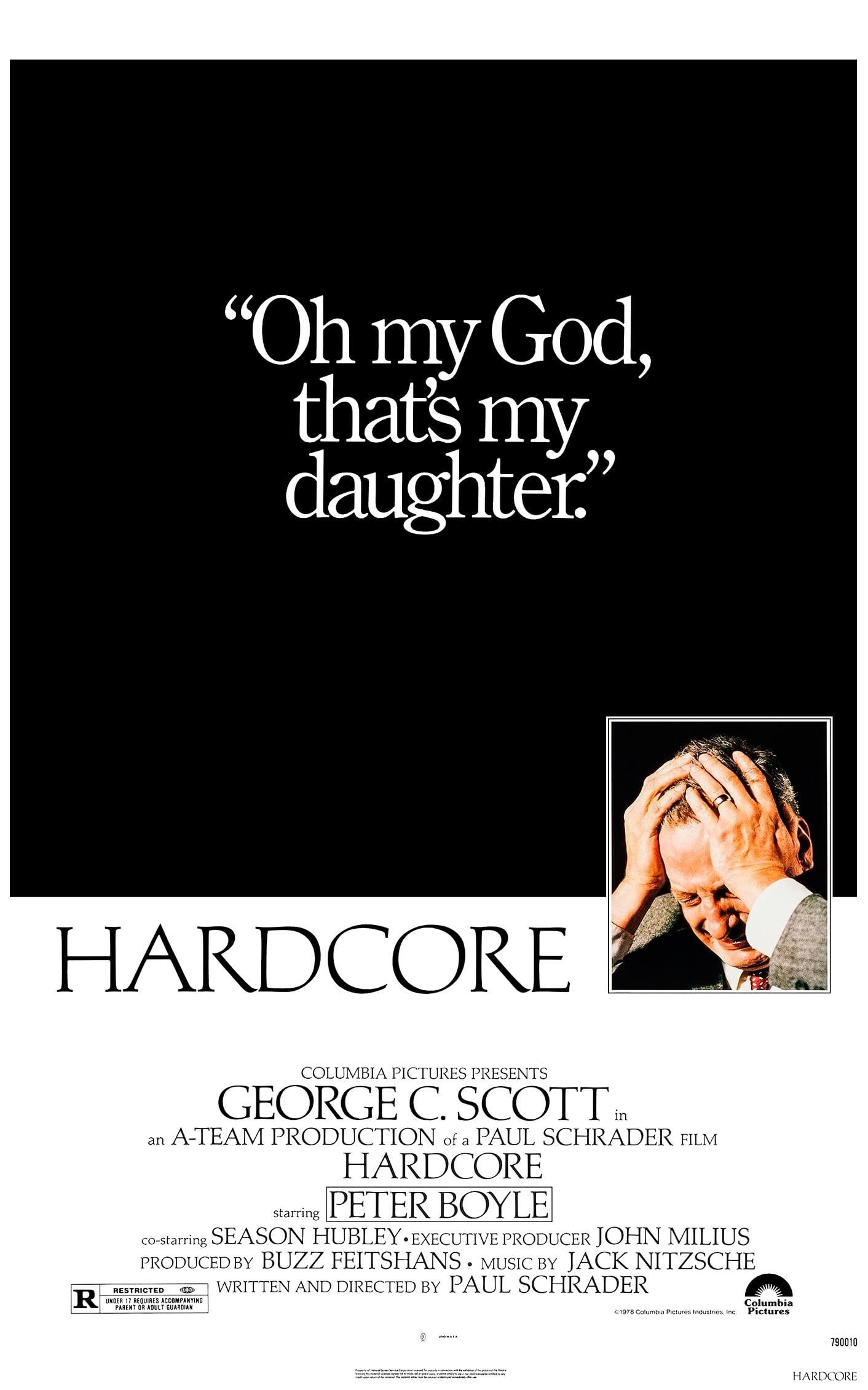

This new-found appreciation has led to myself and others uncovering Schrader’s oeuvre and viewing previous films of his that had, perhaps, been a little lost to time. It was actually a post on twitter about the film’s magnificently dark poster (left) that led me to Schrader’s fantastic 1979 thriller; Hardcore. Hardcore combines the worlds of Calvinist religious conservatism and the Californian porn underworld. These disparate elements being smashed together is something Schrader dabbles with in his later career – religion and eco-anxiety in First Reformed, card counting and treatment of POWs in The Card Counter, horticulture and white nationalism in Master Gardener – and works fantastically at the heart of Hardcore. The film follows George C. Scott’s Jake Van Dorn, a Calvinist businessman from Grand Rapids, Michigan, the heart of the Dutch Reformed Church in America (and the place of Schrader’s own upbringing). Jake is a single father to the quiet Kristen, who is preparing to take a church-sponsored trip to California. However, when Kristen doesn’t return from the trip, Jake is alerted that she has gone missing. By way of Peter Boyle’s fantastically sleazy PI and an 8mm stag film (the stomach-churning scene used for the film’s poster) Jake soon discovers Kristen is involved in the underground ‘porno pits’ of California.

“Least you get to go to heaven. I don’t get shit.”

– Niki (Season Hubley)

I was surprised by how much of a sympathetic view the film took towards religion and Calvinism, perhaps in part due to Schrader’s own conservative Calvinist upbringing. The porn world is more clearly viewed as bad in the film, partly due to it being over 40 years old and society’s changing attitudes. But I think it has more to do with, again, Schrader’s religious upbringing. While elements of the film, like Season Hubley’s sex-worker Niki, are portrayed sympathetically, the massage parlors, snuff films, and sex dungeons George C. Scott’s Jake descends into are lit in a hellish, otherworldly neon. Schrader may not have gone on to be a Calvinist minister but some of their teachings stuck with him. Schrader also clearly respects followers of the church, like Jake, although he does manage to use the film to question the contradictory Calvinist TULIP beliefs. Hardcore is not preachy though, and Schrader’s typical brand of blackly comic nihilism is present throughout the film – as it was in his screenplay for Taxi Driver. There’s a sequence in the film where Jake impersonates a porn producer, wearing garish clothes and a fake hairpiece, to interview male actors who may have starred with his daughter. The scene, like many others in the film (especially the Peter Boyle scenes) is genuinely funny – but never to the expense of the drama.

George C. Scott is fantastic in the film, despite reports him and Paul Schrader did not get on during filming. It’s a difficult job, to make such a devout character likable, but Scott’s realistic and grounded performance does just that. Another actor may have made it difficult for audiences to buy the aforementioned sequence where Jake disguises himself as a porn-baron. But Scott’s grounded portrayal of a father willing to do anything means you believe in everything he does. There’s a turning point late-on in the film, during a violent confrontation with Niki, where I began to find Jake less likable. But the character was still sympathetic and I still wanted him to succeed on his violent crusade. The supporting cast round the film out nicely with Peter Boyle’s sleazy PI being a scene stealer and Season Hubley’s Niki bouncing off Jake’s would-be-father-figure wonderfully. It’s Scott’s film though, and his bravura performance at the film’s centre is a career best.

Schrader has not been kind to Hardcore over the years; in the film’s commentary track he belabors the studio mandated ‘happy’ ending as well as certain aspects of the film’s look. Hardcore’s cinematographer, Michael Chapman (who worked with Scorsese on Taxi Driver) criticises the finished product in an interview about the film (featured on the blu ray’s special features). He wanted a much more grainy, low-rent look to the film, as opposed to the polished neon drenched nights and bright Californian days. I found all of this pretty surprising to hear, as I think Hardcore is fantastic, and the look of the film is up there with the best of the American cinema in the 70s. The ending works brilliantly too, allowing for Jake, on the surface, to achieve what he set out to achieve and rescue his daughter. However, dig a bit deeper into the subtext, into Jake’s absent wife, the flat expression of his daughter, or Jake’s repeated examples of being quick to anger, and you realise the ‘happy’ ending is anything but. Some of these are intentional and some might be accidental (I think Ilah Davis, who plays Jake’s daughter, may just be a poor actor) but it all works together to create a film and ending that lingers with you long after it finishes. I wouldn’t want to disagree with Schrader about many things, especially not his own film. But I do think he’s wrong on Hardcore, and it should be remembered as one of the major works of the late 70s.

Buy Hardcore on Blu Ray here

Reviewed by Tom